Posts Tagged ‘Love in the Land of Dementia’

An Old-Fashioned Holiday

This old-fashioned holiday story from Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey celebrates the spiritual aspects of living with dementia.

When I walk through the doors of the nursing home, I find my mother in her wheelchair, right in front of the medication cart, right behind the central nursing station, where nurses, delivery people, staff and family members congregate. Mom is bent over, her baby doll lying across her lap. When I walk up to her, I ratchet up my energy and widen my smile. I am preparing to clown her into a reaction.

Later my father will ask if I think she recognized me.

“No,” I will have to tell him. “She did not recognize me. But she did smile.”

The smile is important.

My hand waving and head bobbing does its work: Mom does smile, and I can tell she is in her own current version of a good mood.

“Music in the dining room,” the activity board reads, so I wheel her in that direction. An elderly man with a red and white trimmed Santa hat passes us in the hallway.

“Look Mom, there’s Santa,” I tell her.

Having been brought up Jewish, Mom never was all that enthralled with the Claus mythology and she has not changed.

A white-haired woman is in the dining room, busily setting up for the music program. Several patients are already gathered. The woman takes out a microphone, a boom box, an illuminated plastic snowman, and a small silver bell. I continue wheeling Mom down the far corridor, liking the sense of companionship I have from this movement.

As we stroll, a nurse carrying a plate of lettuce walks past us.

“She must have been a good mother,” she says, nodding at the way Mom is holding the baby. “She must still be a good mother.”

“She is,” I say.

I have never really said to my mom, “You were a good mother.”

Now I realize she was.

I can see that Mom is enjoying the ride. She loved movement when she was younger and was far more adventuresome than Dad when it came to airplanes, ski lifts, fast cars, and speedy boats. For her, biting breeze across the face was thrilling, not threatening. Until she became a mother, that is. Then she abandoned her pleasure in the heights and speed and concentrated on making sure we were slow, safe, and centered.

We roll back into the dining room just as the show is ready to start. The singer, Thelda, kicks off her shoes and presses play on the boom box. Above the cheerful sound track, she sings Jingle Bells. She dances across the room with the remnants of ballroom steps. She stops in front of Mom and sings right to her. She gets on her knees, so she can look into Mom’s eyes, and keeps singing. Mom notices her and smiles a little.

Thelda moves on, singing to each of the patients gathered around, so intent on making a connection that she often forgets the words.

“Is it all right for your Mom to come to Christmas holiday events?” the activity director had asked me, when Mom moved from the memory care into the skilled care portion of the nursing home.

“Yes, I’d like her to go to any activities. She likes the extra energy.”

I think Mom would approve of my decision, even though she has never celebrated Christmas. Growing up, her immigrant mother held on to the Jewish spirit of her home, kneading dough for Friday evening challah, observing each holiday and prayer period in her own way. Some orthodox women followed the religious law that commanded a small piece of the dough be burned as an offering to God. My grandmother was poor; she did not believe in burning good food, regardless of tradition. So she sacrificed a portion of the dough to her youngest daughter, my mother Fran. She created a “bread tail,” leftover dough that she smeared with butter and sprinkled with sugar and baked. When Mom used to talk about her mother, she always mentioned this special treat.

Even when I was growing up, and we were the only Jewish family in our neighborhood, my mother still did not sing Christmas songs. She did not willingly go to Christmas parties. She let the holiday rush by her, like a large train, whooshing past, ruffling her hair and leaving her behind.

Now, I am singing Christmas carols to my Mom for the first time. She is smiling, though really not at me. But I am sitting beside her while she is smiling and that makes me happy. She has moved beyond the place where the religions are different, beyond the place where she wants to separate the dough and make a sacrifice for tradition. Her new tradition is anyone who can make her smile.

With each song, from White Christmas, to Silver Bells, to Frosty the Snowman, Thelda moves back to Mom, tapping her, nudging her, shaking a bell almost in her face, acting sillier and sillier. Each time, Mom lifts her head and widens her mouth for a second.

For her finale, Thelda puts on a big red nose and sings Rudolph. When she dances in front of Mom with that nose, Mom laughs. For several minutes, Mom stays fixated on the scarlet nose, her face a miracle in pure enjoyment. I laugh too, so delighted to see Mom engaged and absorbed. Then, Thelda dances away and Mom’s face glazes back over.

Two weeks from now, I will bring a menorah and candles into my mother’s room. My father and I will have a short Chanukah ceremony with Mom. She will pick at the shiny paper covering the Chanukah gelt (chocolate candy disguised as money). She will slump over in her chair. But she will come back to life when she sees me, her only daughter, wearing a big red nose as I light the menorah.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Connecting in the Land of Dementia: Creative Activities to Explore Together and Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Celebrating our Mothers

If my mother were still alive, I would be taking her roses and chocolate this Mother’s Day. She would be delighted and her delight would magnify when my daughters and her great-grandchildren arrived. Love is such a beautiful glue, such a simple and strong way to stay connected. I wanted to share this story from Love in the Land of Dementia, as a way of celebrating our mothers.

The Woman She Was

My friend Karen gives me a gift: she says, “Tell me about your mother.”

My friend Karen gives me a gift: she says, “Tell me about your mother.”

We are sitting in a quiet mid-afternoon café and I let the question sink into me.

When friends occasionally ask me, “How is your mother doing?” I have different answers, depending on the situation. If we are in one of those conversations that are like confetti in brisk wind, I say, “She’s okay.”

If we are sitting across from each other and my friend is looking right at me, I answer, “She’s pretty deep into Alzheimer’s.”

“Does she recognize you?” she might ask.

“No, but she may recognize I am a person she likes,” I answer.

That usually ends that conversation.

But “Tell me about your mother,” is an invitation I don’t usually get.

“What would you like to know?” I ask.

She stirs her iced mocha. “Whatever you want to tell me,” she says softly. “I would like to know about her life and her interests.”

Since my mother has been in the nursing home with Alzheimer’s, I have seldom talked about the person she used to be. Occasionally my father and I reminisce about family vacations and outings. I sometimes ask Dad questions about our growing up days and the early days of their courtship. But I rarely think about the woman I knew all my life, the mother, grandmother, artist, gardener, compassionate friend, avid reader, bird-watcher, early morning walker, lemon-meringue pie baker. That woman is gone and I have spent a lot of energy learning to know and appreciate the woman who now commandeers her body.

As I consider what I want to tell Karen, I remember visiting my mom’s best friend, Bel, in California when I was a teenager. Bel, who was spunky and adventurous in a way that seemed so different from my conservative mother, drove me from Berkeley to the small resort where I would work as a chambermaid for the summer.

As I consider what I want to tell Karen, I remember visiting my mom’s best friend, Bel, in California when I was a teenager. Bel, who was spunky and adventurous in a way that seemed so different from my conservative mother, drove me from Berkeley to the small resort where I would work as a chambermaid for the summer.

“Do you know how I met your mom?” she asked me, as we drove down the winding roads, past fragrant stands of eucalyptus trees.

“In Iceland, during the World War II,” I said. I had heard stories of the two of them taking a break from their work in the hospital by skiing, then stopping for a soak in a hot springs.

“No, we met earlier in Chicago. We were both nurses working the twelve-hour night shift. The hospital had a room with a couple of bunk beds so we could rest on breaks. One night I walked in there and heard the most heart-breaking sobbing. It was Frances, crying her eyes out. I asked her what was wrong and she said, ‘Nothing.’”

I smiled. That sounded like Mom, never wanting to admit anything was wrong.

“Then I asked her again and she sobbed out that her husband Sam had died six months ago from pneumonia. She was so sad she didn’t know if she could go on. A bunch of other nurses and I were going to Florida for a short vacation and I persuaded your mother to join us. But as it turned out, we never went; a week later I decided to join the Army and I encouraged her to come along. We’ve been best friends ever since.”

When I heard this story at the age of seventeen, I was too young to fathom my mother’s grief and despair. By the time I told Karen the story, I had some sense of what my mother must have gone through.

“Your Mom was really brave, to serve in the Army during wartime,” Karen says.

I feel a little swell of pride. Mom’s tales of traveling in the darkest night on the troop ship, with bombs falling nearby, were so familiar I had never considered her bravery and courage.

Now I tell Karen how my father, encouraged by Bel’s husband, wrote Mom a letter, telling her he was ready to marry a nice Jewish girl. Was she interested? Was she available?

Now I tell Karen how my father, encouraged by Bel’s husband, wrote Mom a letter, telling her he was ready to marry a nice Jewish girl. Was she interested? Was she available?

After some correspondence, Mom surprised herself by agreeing to meet him in Chicago. At the end of the week, my father asked her to marry him. She considered the offer for three weeks and accepted. Their whirlwind romance was fueled by practicality.

“What a great story,” Karen says. “Your mother must be an amazing woman.”

Sparked by Karen’s interest, I let myself feel my love for my mother as she used to be. I am in tears by the time our conversation ends.

“Thank you for asking me about my mother,” I say to Karen.

“Your stories make me want to call my own mom and hear her stories again.”

As I drive home, I think of more “mom” stories to share with my children and my brother. I see myself, along with my brother and father, as the carrier of my mother’s sacred legacy. I imagine myself tenderly fanning the embers, adding dry leaves and crumbled paper, creating a blaze with each memory. I realize I don’t have to give up Mom’s old self: I can be her historian and her scribe, carrying her stories with me, and making sure they live on.

Inside Dementia: Finding Gifts in the Journey

“My husband and I have been married for 53 years,” a woman with delicately curled silver hair and mournful eyes told the group. “But in the two years since he was diagnosed with dementia, our relationship has changed.” She dabs at her eyes with a tissue and takes a breath. “It has grown even stronger. We are closer than we’ve ever been.”

Ron and I were in a conference room of caregivers in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, presenting for the Greater Indiana Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association. We had just shared my story, Love in the Land of Dementia, and we were all talking about the gifts we have found in the dementia journey.

Another woman, whose husband was newly diagnosed, talked about her frustration and impatience before the diagnoses.

“Now that I understand what is going on, I have vowed to be more patient. I don’t want to waste a minute of our time together.”

“My husband doesn’t know who I am right now,” another woman said. “But the other day, he gave me such a compliment. He told me, ‘I want to marry you.’”

She told us how she rummaged in her cedar chest and showed her husband their marriage certificate. He read it with interest. Then he looked at her, eyes shining, and repeated, “I want to marry you.” Those words, so filled with love, lifted her spirits immeasurably. “To think that even now, when he doesn’t remember much of our lives together, he still loves me so much, that means a lot to me.”

She smiled, as we all applauded this amazing love.

We heard more stories of amazing love at our earlier presentation in Merrillville, Indiana. When we talked about the gifts and blessings we had each discovered in the dementia journey, one woman told us, “I find it an honor to take care of my mother. She has done so much for me and I am lucky to get to care for her right now. I am glad to be able to show my unconditional love for her.”

We heard more stories of amazing love at our earlier presentation in Merrillville, Indiana. When we talked about the gifts and blessings we had each discovered in the dementia journey, one woman told us, “I find it an honor to take care of my mother. She has done so much for me and I am lucky to get to care for her right now. I am glad to be able to show my unconditional love for her.”

People shared many blessings—patience, the increased ability to live in the present, gratitude, flexibility, humor—but a deepening of love was the overarching message. We felt it during our own caregiving journeys, and we felt it deeply in the presence of those caregivers.

“The best and most beautiful things in this world cannot be seen or even heard, but must be felt with the heart.” Helen Keller

To learn more about the work the Greater Indiana Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association is doing, please visit : https://www.alz.org/indiana/

The Secret of Art-Power: Imagination Rules

This is a story celebrating the arts and creativity, an excerpt from my book Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

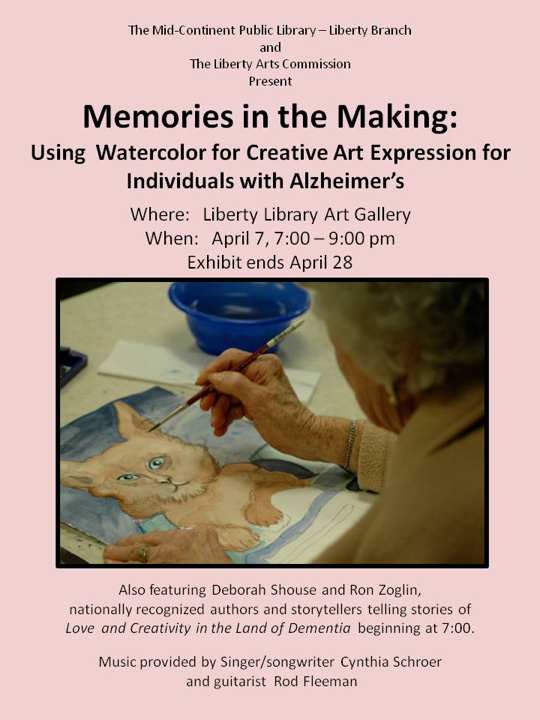

We are delighted to be presenting a program in partnership with the Liberty Library Art Gallery, the Liberty Arts Commission, and the Heart of America Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association. If you’re in our area, please feel join us.

The Hills Are Alive

I miss my mom and decide to attend a Memories in the Making art class, designed for people who are living with dementia. I want to meet some of the artists and feel my connection to Mom, who was an avid painter in her earlier years, through the artistic process. Still, I feel nervous as I walk through the nursing home and into a small activity area.

“We have a visitor today,” Harriet, the facilitator, tells the assembled group.

Everyone looks up.

“Come paint with us,” a woman says.

I smile and begin to relax. Harriet hands me bowl of water, paper, brush and watercolors and finds me a place. Then she introduces me to the artists.

Ed, a former veterinarian, has a photograph of a great blue heron in front him. He is a slight, spry man who looks like he could fix any emergency.

“That bird is really coming along,” Harriet tells Ed. Using colored pencils, he has sketched the upper half of the heron. The bird has an inquisitive look. Now Ed is concentrating on drawing an assortment of cattails, reeds, and other marsh plants in the background.

“Ed is married to Rhea,” Harriet tells me, as I look at the splash of free-form color on Rhea’s page. Rhea, who also has Alzheimer’s, is creating a sunset with vivid oranges and purples. I smile at the difference in their art—Ed’s controlled sense of detail, Rhea’s spontaneous bursts of color. I imagine those traits made for a good partnership.

“We’ve been together twenty-two years,” Rhea says. She has a plump welcoming look about her. “Or maybe it’s twenty-five years. Do you remember?” she asks Ed.

“A long time,” Ed says.

Norman has beautiful silver hair, deep brown eyes, and is dressed in a Polo shirt and slacks. He looks like he could easily be running a meeting or entertaining important clients on the golf course. Formerly an engineer, he was living in New Orleans, Harriet explains, and was moved up here to be near family. He is recreating a mountain lake scene and has quickly captured the essence of his photograph.

“I just use my fingers to gauge the perspective,” he tells me, when I compliment his work. In his spare time, Harriet says, he is recreating maps of area bridges.

“I just use my fingers to gauge the perspective,” he tells me, when I compliment his work. In his spare time, Harriet says, he is recreating maps of area bridges.

As I sit down to my own paper and watercolors, I hear someone from the room next-door singing, The Sound of Music.

Harriet sings along and we chime in. As I paint, I feel a sense of connection. Harriet knows how to create a space where the artist can blossom.

Harriet starts a verse of Over There and everyone joins in.

After some time, Harriet says, “It’s almost time to stop for today.” I take a final walk around the table. Ed’s heron looks ready to enter an Audubon competition. Rhea’s sunset is colorful and dramatic. Norman’s hills look complete and his lake is taking shape. My own painting looks plain and unsophisticated next to the rest of the art.

“Have any of these people had art lessons before?” I ask, as I help Harriet empty water bowls and clear away used paper towels.

“No,” she tells me.

For most of these artists, this is a tender and uncertain time, a period when memory and rational thinking are often  blotchy and blurred, where words can fall away as quickly as autumn leaves. This art program gives them a chance to express themselves freely and creatively. Out of the mental chaos and confusion, the art emerges, vibrant, true, and exciting.

blotchy and blurred, where words can fall away as quickly as autumn leaves. This art program gives them a chance to express themselves freely and creatively. Out of the mental chaos and confusion, the art emerges, vibrant, true, and exciting.

As I am taking leave of Harriet, Norman comes back into the room.

“Is there white?” he says. “I’m going to need white for the snow on the mountain tops.”

“I’ll have some for next time,” Harriet promised. “Meanwhile, would you like one of these white pencils?”

Norman takes the pencil. “The snow makes all the difference,” he tells me. His walk is steady and sure and he leaves the room humming, “The hills are alive.”

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Three Tips for Living Large Inside the Box

How can we all stay connected with our creative spirits during the dementia journey?

I’ve been very inspired by people who are connecting both with care partners and with those living with dementia, through artistic and creative expression. I recently read this blog by Matt Stevens, a designer and illustrator based in Charlottesville, NC. Best known for his MAX100 project, 100 interpretations of the same object (the Nike sneaker). Matt has also worked on identity and branding for clients such as Pinterest, Facebook, Evernote, Dunkin’ Donuts, and the NBA. His thoughts on creativity and repetition seem applicable to the care partner’s journey.

How Rules and Repetition Inspire Creativity

For centuries, artists have been exploring the benefits of working with constraints. Bach composed the Goldberg variations — an aria and 30 variations for a harpsichord — in 1741. Picasso created an 11-lithograph series of bull illustrations in 1945. Matt Stevens reinterpreted the same object in his MAX100 project and has serialized a number of his other works as well. Great artists and designers impose constraints to inspire their creativity.

“I noticed how often I create repetition in my work – systems for myself to operate within,” Matt says. “I asked myself: Why do I create this repetition? Why do I love series so much?”

Limitations force you to be inventive and create new paths.

With Matt’s MAX100 project, he focused on a single image — the iconic Nike sneaker — and reinterpreted it 100 times.

The rules were simple: the shoe had to be in the same position on the page (it couldn’t be turned), and it had to be fundamentally changed. It wouldn’t be enough to add patterns around it: he would iterate on the shoe itself, over and over again.

“The idea is to take something, abstract and change it and let the narrow focus of the project give you a sense of freedom as you move through it. How far could I push it? How much could I abstract it?”

For Matt, this exercise led to a successful Kickstarter that turned into a book, client work with Nike themselves, plus an art exhibition in New York. #

From Deborah.

One of the ways I tried to learn from creative limitation was exploring new ways to answers my mom’s repetitive questions. I also experimented with new ways to bring joy and creativity to our time together in the care home. Even though Matt’s tips are targeted towards the artistic community, I find them thought provoking and hope you will too.

Here are a few more ideas from Matt:

No project happens overnight. Your process for setting a project with the right limitations is important.

- Define the problem

Choose your subject and your challenge. You may be trying to understand a fellow designer’s technique. You may really just love an icon. You may want to learn a new skill. Define the problem and what you will focus on. The MAX100 project, for instance, started as a project for Matt to learn more about illustration.

- Limit your options in solving the problem

“Limited options provide clarity. And when you get stuck, sometimes the answer is not more; but it’s less.”

Impose a structure and set some rules to explore your concept. What rules will you create by? Create a baseline structure to operate within, whether that’s the medium you are trying to learn, or the logo you are trying to explore.

- Iterate, explore, learn, repeat

Don’t get stuck on the unknowns. Don’t be afraid to imitate the styles of people you admire as you go, either: these can set off their own series of explorations. Pick those apart and understand how they work. You may start to see the task in new and unexpected ways, and explore anew from there.

Remember that when you get stuck, sometimes the answer is not more, but less.

To learn more about Matt Stevens, visit

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

The Marvels of Movement

Dancing is like dreaming with your feet! ~Constanze

During my mom’s dementia journey, movement often inspired and connected us. Here is one of those magical moments, excerpted from my book, Love in the land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey. The story is set in my mom’s memory care unit.

**

Rochelle, the activity director, sticks in another tape and soon Stardust is playing.

“Let’s dance,” she says, motioning everyone to stand.

Mom looks up and I offer her my hand.

“Want to dance?” I ask her.

“What?”

“Want to dance?” I repeat, making a swirling motion.

“What else,” she says, standing up.

My parents have danced to this song many times, my mother coaxing my father onto the dance floor. I hold hands with Mom and move back and forth to the music. She laughs and does the same. I twirl her, and she walks around in a jaunty little circle. For a moment, her energy and charm have returned. I feel like I have found my long-lost mother. If my father were here, he would not be surprised. He is certain she will return to him and takes every word, every gesture of affection, every smile as a sign of hope.

“Hope is everything,” Dad told me just last week. “I find something hopeful and I milk it for all it’s worth. If it doesn’t work out, then I search for something else. Otherwise, I am in despair.”

I twirl my mom again. It is actually our first real dance together …

***

I loved my dance with my mother for the deep connection it gave me. My friend Natasha Jen Goldstein-Levitas reminds me of the other benefits of movement. Natasha is a Philadelphia, PA based Registered Dance/Movement Therapist (R-DMT) and Reiki Practitioner who does heartfelt and creative work with those living with dementia. She writes: “Among the creative arts therapy modalities, dance/movement therapy (DMT) offers the opportunity for individuals to express themselves, regardless of functional level. DMT engages the sensory systems and stimulates the physical, emotional, and cognitive areas of functioning. This movement is also a wonderful outlet for care partners.”

Samuel Beckett sums this up, He says, “Dance first. Think later. It’s the natural order.”

To read Natasha’s blog, please visit:

http://blog.adta.org/category/creative-arts-therapy/

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Doing the Work of Our Hearts

I woke up in the middle of the night with the answer I’d been seeking: I would self-publish the book of essays I had written about my journey through my mother’s Alzheimer’s and I would donate all the monies from the book to Alzheimer’s research and programs.

It was the summer of 2006, and for weeks I’d been wrestling with a question:

Should I seek a traditional publisher or independently produce the book? Both seemed daunting; in the past, I had primarily written books for and with other people and publication wasn’t my problem. But this book, Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey, was the work of my heart, born out of my desire to stay connected with my mother and find the joys and blessings in her experiences with Alzheimer’s. I wanted to share my stories of hope so they might help other caregivers.

“What about donating a portion of the proceeds?” my partner Ron asked. I was already making a marginal living; Ron’s suggestion was practical but I shook my head.

“I think I’m supposed to donate it all,” I told him. “That way, instead of selling a book, I’ll be raising money for a cause I’m passionate about.”

I talked through the details, consulting knowledgeable friends, an attorney and our local Alzheimer’s Association. My mission: to use the book as a catalyst to raise $50,000 for Alzheimer’s. There was one glitch; I estimated the cost of designing and printing could be in the thousands. Where would I get the money? But even though I was often worried about funds, this hurdle didn’t bother me. My intuition was strong. I was supposed to do this and would raid my savings if needed. Ron was excited about the project and pledged to work with me and help me make it happen.

“We will also help you,” my friends Rex and Jane said. They had shepherded several books through production and were extremely savvy. Plus, they wanted to be part of my mission.

Over the next months, Ron and I spent hours with Rex and Jane, working on design, cover, production and print details. Endlessly patient, they were dedicated to creating the book I envisioned. And they kept their fees to a minimum.

When the finished product arrived months later, I felt a sense of pride and completion. The beautiful cover featured one of my mother’s paintings, the type was easy to read, the interior design inviting.

Ron and I had often performed my stories together, and we began speaking and sharing stories from the book with Alzheimer’s associations, healthcare professionals, caregivers’ groups and others. When we traveled, we reached out to Alzheimer’s groups to set up speaking engagements. We were always moved and inspired by the people we met.

“The person with Alzheimer’s is the pupil in God’s eye,” the priest in a fourteenth-century church in Florence, Italy told us.

“Your story is my story,” a man in Istanbul, Turkey said.

“I’ve been caring for my mother for ten years,” a woman from Brooklyn, New York said. “It has been the most meaningful experience in my life.”

“When I learned Mama had dementia, I quit my job in Houston and moved back home,” a woman in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands said. “I wanted my children to know their grandmother in all the stages of her life and I wanted to be here to care for her.”

Sometimes we spoke in front of hundreds of people; other times we talked to groups of ten. When possible, we brought books and people often donated more than the suggested fifteen-dollar price, knowing that all the proceeds went to Alzheimer’s research and programs.

By 2011 we had done it! We had raised $50,000 for Alzheimer’s. But we kept going; we were still learning and growing. The work was healing for both of us and we loved connecting with other caregivers.

In 2012 I was ready to give the book a wider distribution and reached out to Central Recovery Press. They published an enhanced edition in 2013. Today, our fundraising journey continues as we donate a portion of our proceeds to this important cause.

The self-published version of Love in the Land of Dementia served as a catalyst for raising more than $80,000 for Alzheimer’s programs and research. My stories of looking for the blessings in the journey reached thousands of people, fulfilling my goal of making a contribution to the world. And the bonus was that both Ron and I had changed.

By following our intuition and doing the work of our hearts, we became more compassionate, understanding and trusting.

by Deborah Shouse