Inspiration

One Potato, Two Potato

The next three blogs are dedicated to the holiday season. This story just appeared in Chicken Soup’s new Merry Christmas book. Here’s to each of us sharing our light in the world.

The Latke Legacy

“This is not like Mom used to make,” I had to confess. It was my first Chanukah of being the latke lady. My mother’s potato pancakes were crisp, flat, and nicely rounded. The texture was smooth but not mushy and they shone with just a glint of leftover oil. I had been a latke apprentice for years, pressed into service by Mom. I was a key cog in the labor pool, peeling the potatoes, then wearing out my arm rubbing them against the stainless steel grater, using the side with the teardrop shaped holes. My mother must have known that enlisting my help would keep me from pestering her to make potato pancakes for other occasions. Only once a year did these delicious patties grace our table, when we lit the first candles of Chanukah and began the eight-day Festival of Lights.

My debut latkes were pale and greasy, like something carelessly served in a late night diner. I myself was pale and greasy from the stress of trying to coax the patties into cohesion. First they had drifted apart—too little flour. Then they had turned cliquish, glomming into militant lumps. When I had finally worked through the potato/flour/egg ratio, I bumped into the complex dynamic between potatoes, oil and heat. For three hours I had struggled to create this barely edible token of tradition.

Years passed. Every Chanukah, I faced a different challenge. The oil was too cold, too hot, not enough, too much. The texture was too coarse or too fine. The grated onions were too strong or too weak. The latke mixture was too thin then too thick. Every year, I hoped for pancakes that tasted like Mom’s and got instead grey leaden latkes. My daughters, who peeled and grated potatoes with me, examined my finished product warily, smothering it in the traditional applesauce and often taking only a few bites. I worried that when they grew up, they would forego the holiday tradition and turn to something simpler and more delicious, like frozen hash browns. I felt a sense of failure as a mother and as a tender of the tradition. My mother had shown me how to make the latkes: why couldn’t I measure up and instill the potato pancake protocol in my progeny?

Then my daughter Sarah, fresh from college and a first job, moved back to town and offered to help me prepare the holiday meal. She was a food channel devotee and had already orchestrated several dinner parties, creating the menus and cooking all the courses. She understood the relationship between vegetables, oil and heat.

“Mom, I think you need to squeeze more water out of the potato mixture,” she advised. “Maybe you could use a food processor to grate the potatoes. What if you used two pans instead of trying to cram so many into one?”

I stepped back and she stepped forward and under her guidance, we prepared the latkes. As I watched my daughter mastermind the cooking, I realized that tradition could be kept alive in many ways. My daughter was starting the tradition of “doing what you’re good at,” giving me a chance to forget my own culinary challenges and applaud her self-taught abilities.

That Chanukah night, everyone at the table oohed and ahhed at the sight of the latkes. Each one was golden brown and crisp, free of extra oil. I didn’t even have to secretly search and pluck out a “good one,” like I had been forced to do in previous years.

I looked around the table of friends and family and took a bite of my daughter’s latke. My mouth filled with the crunch, flavor and intriguing texture of a of well-fried potato pancake. This was the latke I had been waiting for; just like Mom used to make. Only better.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

.

Eight Steps to Help People Living with Dementia Feel at Ease during Holiday Gatherings

As we move into the holiday season, Ron and I think often of our parents who went through their last holidays with dementia: my mom Frances and his father Frank. We wanted to share the season with them in ways that felt safe, comfortable, and honoring so we gradually developed these tips. Recently, we shared them via email and had such a great response we also want to share them with you.

Several people wrote, “These tips are good for anyone, not just those with memory loss.”

What great wisdom–to treat each person with the tenderness and consideration that we often reserve for someone going through a physical or emotional illness.

We’d like to share our tips and we’d like to learn from you: what other suggestions do you have for helping people feel connected at gatherings?

Eight Steps to Help People Living with Dementia Feel at Ease during Holiday Gatherings

- When you’re in a group, help the person living with dementia feel safe and comfortable by having a trusted friend or family member stay beside him or her, explaining the proceedings and fielding questions from others, as needed.

- Encourage people to say their name and maintain eye contact when conversing with the person who is living with dementia.

- Make sure the person can come and go from the group as needed. Create a quiet space where he or she can rest — or appoint a caring person to drive your loved one home when he tires of the festivities.

- Have something special for them to look at, like a family photo album or a favorite magazine.

- Choose background music that is familiar to them, music of their era played in a style they resonate with.

- Prepare a few of their favorite foods.

- When talking to them, don’t correct or contradict or try to pull them into the current reality. Simply listen carefully and let them talk.

- Appreciate them for who they are right now.

Here’s to a holiday season filled with grace, gratitude and generosity.

Creating Personal Stories from the Care Partner’s Journey

My mother’s Alzheimer’s drove me to write. My writing inspired me to speak.

Over the last years, I have received enormous pleasure from connecting with people all over the world, sharing the stories from Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

It All Started with Grief

When I initially realized the depth of my mother’s memory loss, I was shattered with grief.

My initial reaction was:

Visit with mom.

Drive home, wiping tears from my cheeks.

Stumble into the house, walk into a chair or table, and misplace my car keys.

Sit at the dining room table and stare numbly into space.

One day, during the “staring numbly” phase, my partner Ron said, “Are you writing down your feelings?” It was a smart and sensible thing to say; the sort of suggestions I might make to him in a crisis. I was, after all, a writer.

“I don’t feel like writing,” I said.

But his words stayed with me. The next day, I slightly altered my behavior.

Visit with mom.

Drive home, wiping tears from my cheeks

Stumble into the house, walk into a chair or table, and misplace my car keys

Sit at the dining room table and write numbly for 20 minutes

Pouring my Emotions Out and Inviting Understanding In

I poured out my fears, anger and grief. After doing this for a week,

I began noticing how interesting my visits with Mom were; we were explorers on a wild inner trek.

I started documenting our time together, sometimes even taking notes during my visits. I wrote about the challenges, humor and blessings. I wrote about my conversations with my father, with friends and family and with the aides, the nurses, the social workers. As I wrote, I saw there was much hope, promise and energy in my new world.

As I shared my work with friends and family, I realized I was chronicling my mom’s last years and capturing part of our family history.

Putting Your Life on the Page

How do you take a challenging part of your life and bring it to the page? Here are a few simple tips:

Pour Out Your Feelings

Give yourself time to feel your emotions, whether it’s through writing, art, music or other. Writing down your feelings helps you understand the depth of what you’re going through. For me, writing helped change my fear into curiosity.

Notice the Details

Write down the particulars, noting simple concrete facts. You are a researcher collecting data.

Uncover the True Story

Look for the universal meaning in your specific experience. How have you changed? How will the reader change through reading your words?

Ask for Feedback

Read the story aloud to someone and see how it sounds. What’s working and what’s missing? Ask colleagues for a professional critique. Think over their advice and decide what is right for you.

I was lucky enough to read some of my stories to my mother and father and receive their blessing for my work. Anytime I featured people in a story, I shared it with them to make sure they were comfortable with the material. When they’re comfortable, it’s time to share with friends and a wider audience, if you wish.

Here are some writings from other people on this journey.

Vicki Tapia’s memoir, Somebody Stole My Iron, details the daily challenges, turbulent emotions, and the many painful decisions involved in caring for her parents. Laced with humor and pathos, reviewers describe the book as “brave,” “honest,” “raw,” “unvarnished,” as well as a “must-read for every Alzheimer’s/dementia patient’s family.” She wrote this story to offer hope to others whose lives have been intimately affected by this disease, to reassure them that they’re not alone.

Vicki Tapia’s memoir, Somebody Stole My Iron, details the daily challenges, turbulent emotions, and the many painful decisions involved in caring for her parents. Laced with humor and pathos, reviewers describe the book as “brave,” “honest,” “raw,” “unvarnished,” as well as a “must-read for every Alzheimer’s/dementia patient’s family.” She wrote this story to offer hope to others whose lives have been intimately affected by this disease, to reassure them that they’re not alone.

Greg O’Brien’s story isn’t about losing someone else to Alzheimer’s, it is about losing himself. Acting on long-term memory and skill, coupled with well-developed journalistic grit, O’Brien decided to tackle the disease and his imminent decline by writing frankly about the journey. “On Pluto is a book about living with Alzheimer’s, not dying with it.” On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s by Greg O’Brien

Greg O’Brien’s story isn’t about losing someone else to Alzheimer’s, it is about losing himself. Acting on long-term memory and skill, coupled with well-developed journalistic grit, O’Brien decided to tackle the disease and his imminent decline by writing frankly about the journey. “On Pluto is a book about living with Alzheimer’s, not dying with it.” On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s by Greg O’Brien

Jean Lee’s memoir details her journey caring for both parents who were diagnosed on the same day. It is a WWII love story held together by faith and family. Alzheimer’s Daughter by Jean Lee

Marianne Scuicco describes herself as a writer who happens to be a nurse. She writes this work of fiction based upon her care for the elderly. It’s a tenderly told love story about Jack and Sara, owners of a New England bed and breakfast. Sara develops Alzheimer’s and Jack becomes her caregiver. Blue Hydrangeas by Marianne Sciucco

Marianne Scuicco describes herself as a writer who happens to be a nurse. She writes this work of fiction based upon her care for the elderly. It’s a tenderly told love story about Jack and Sara, owners of a New England bed and breakfast. Sara develops Alzheimer’s and Jack becomes her caregiver. Blue Hydrangeas by Marianne Sciucco

Shannon Wiersbitzky writes this work of fiction through the eyes of a young girl, not surprising perhaps, as her author bio notes that her own grandfather had Alzheimer’s. In the story, when thirteen-year-old Delia Burns realizes that her elderly neighbor is beginning to forget, she involves the entire town in saving his memories. What Flowers Remember by Shannon Wiersbitzky

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Six Tips for Surviving the Holiday Season When a Loved One Has Dementia

Normally, Thanksgiving was my favorite holiday, a time our family gathered together at my Kansas City home. But that November, my stomach clenched at the thought of our traditional Thursday evening meal.

My mother had Alzheimer’s and the holiday would be different. I felt alone but of course I wasn’t: there were 15 million family/friend caregivers helping the five million Americans who have dementia.

I’d been through my initial storm of denial and grief. I felt I’d been coping well with Mom’s diagnosis, focusing on offering my father extra support and trying to flow with Mom’s now spotty memory and personality quirks. But a pre-season sadness invaded me in October and I found myself dreading the alleged festivities. How could we have our usual holiday dinner, take our after dinner walks, play Scrabble and Hearts and Charades without Mom’s participation? How could we enjoy going to movies and plays when Mom was having trouble focusing and sitting still? And how would Mom react to the situation: would she feel uncomfortable and out of place? Would Dad feel protective and anxious? And more important, what would we have for dessert! Mom was legendary for her chocolate and butterscotch brownies, date crumbs, and bourbon balls. No store-bought cookies would compare.

As I stewed over the prospect of a depressing Thanksgiving weekend, I remembered the vows I had made: I had promised I would try to stay connected to Mom throughout her Alzheimer’s journey. And I had promised to see the gifts and blessings and fun in the experience.

So I began thinking: if the holiday is going to be different, why not concentrate on making it different in a creative and connective way? Here are some ideas I used to make the holiday work for me.

- Acknowledge my feelings of loss and grief. I wrote them down and shared them with a few friends. Just expressing myself made me feel stronger.

- List what I would miss most during the holiday season. My list included cooking with Mom, eating her brownies and rum balls. I asked my brother, who’s a terrific baker, to make some of our favorite sweets and I set up a place in the dining room where Mom could sit next to me while I chopped mushrooms and peeled potatoes.

- Create an activity to give our holiday a new focus. We created a simple holiday scrapbook called, “The Little Kitchen that Could,” complete with a family photo shoot and a playful script.

- Appreciate my blessings. We started our Thanksgiving meal by asking everyone to name one thing he or she was grateful for. I continued my gratitude practice throughout the holiday season, either alone or with others via telephone and social media.

- Take extra good care of myself. I treated yourself as I would a friend who’d suffered a deep loss.

- Set up a lifeline. “I’m worried about melting down,” I told my friend. She urged me to call anytime for encouragement and reassurance.

These six steps helped me enjoy my holiday and appreciate my mom just as she was. Our holiday was “different” but it was also wonderful.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Three Tips for Living Large Inside the Box

How can we all stay connected with our creative spirits during the dementia journey?

I’ve been very inspired by people who are connecting both with care partners and with those living with dementia, through artistic and creative expression. I recently read this blog by Matt Stevens, a designer and illustrator based in Charlottesville, NC. Best known for his MAX100 project, 100 interpretations of the same object (the Nike sneaker). Matt has also worked on identity and branding for clients such as Pinterest, Facebook, Evernote, Dunkin’ Donuts, and the NBA. His thoughts on creativity and repetition seem applicable to the care partner’s journey.

How Rules and Repetition Inspire Creativity

For centuries, artists have been exploring the benefits of working with constraints. Bach composed the Goldberg variations — an aria and 30 variations for a harpsichord — in 1741. Picasso created an 11-lithograph series of bull illustrations in 1945. Matt Stevens reinterpreted the same object in his MAX100 project and has serialized a number of his other works as well. Great artists and designers impose constraints to inspire their creativity.

“I noticed how often I create repetition in my work – systems for myself to operate within,” Matt says. “I asked myself: Why do I create this repetition? Why do I love series so much?”

Limitations force you to be inventive and create new paths.

With Matt’s MAX100 project, he focused on a single image — the iconic Nike sneaker — and reinterpreted it 100 times.

The rules were simple: the shoe had to be in the same position on the page (it couldn’t be turned), and it had to be fundamentally changed. It wouldn’t be enough to add patterns around it: he would iterate on the shoe itself, over and over again.

“The idea is to take something, abstract and change it and let the narrow focus of the project give you a sense of freedom as you move through it. How far could I push it? How much could I abstract it?”

For Matt, this exercise led to a successful Kickstarter that turned into a book, client work with Nike themselves, plus an art exhibition in New York. #

From Deborah.

One of the ways I tried to learn from creative limitation was exploring new ways to answers my mom’s repetitive questions. I also experimented with new ways to bring joy and creativity to our time together in the care home. Even though Matt’s tips are targeted towards the artistic community, I find them thought provoking and hope you will too.

Here are a few more ideas from Matt:

No project happens overnight. Your process for setting a project with the right limitations is important.

- Define the problem

Choose your subject and your challenge. You may be trying to understand a fellow designer’s technique. You may really just love an icon. You may want to learn a new skill. Define the problem and what you will focus on. The MAX100 project, for instance, started as a project for Matt to learn more about illustration.

- Limit your options in solving the problem

“Limited options provide clarity. And when you get stuck, sometimes the answer is not more; but it’s less.”

Impose a structure and set some rules to explore your concept. What rules will you create by? Create a baseline structure to operate within, whether that’s the medium you are trying to learn, or the logo you are trying to explore.

- Iterate, explore, learn, repeat

Don’t get stuck on the unknowns. Don’t be afraid to imitate the styles of people you admire as you go, either: these can set off their own series of explorations. Pick those apart and understand how they work. You may start to see the task in new and unexpected ways, and explore anew from there.

Remember that when you get stuck, sometimes the answer is not more, but less.

To learn more about Matt Stevens, visit

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Quick Creative Boosts

“I do not know what is going on, but it seems Alzheimer’s stops where creativity begins.” -Person living with Alzheimer’s disease, after creating art

I wanted to do a quick spiritual practice that was aligned with art and I asked artist, art therapist, counselor, and teacher Shelley Klammer for advice.

“Every day, you can simply draw a mandala, a circle, and color it any way you want,” she said.

I liked her idea and began drawing a circle almost daily. Then I have fun filling the inside with crayons, paints, markers, colored pencils, chalk, and pens. Sometimes I create bright designs; other times I draw childlike images—a bunny, a tree, an elephant. With each creation, I feel like I am reclaiming my love of drawing that I had set aside years ago because I “wasn’t very good at it.”

The repetition of the circle gives form to whatever art drifts out of me, just as the repetition inherent in the role of care partner holds a space for creativity.

How are you adding creativity to your every day life?

For more about Shelley and her work, please visit

http://www.expressiveartworkshops.com/

“We have to continually be jumping off cliffs and developing our wings on the way down.” ― Kurt Vonnegut, If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?: Advice for the Young

“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and will be lost.” ― Martha Graham

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Rock with Rhymes that Resonate

The audience was quiet, partially because some of the people were slumped over in their wheelchairs, eyes closed. Gary Glazner stood in front of the group, wondering if he could engage them. He had received a grant to offer a poetry workshop in a memory care unit and he had carefully selected several familiar poems. He’d introduced himself to everyone and he was ready to inspire people through reading poetry. But were they ready for him? He took a breath and began.

“I shot an arrow into the air,” Gary said to the seemingly comatose group.

“And it fell down I know not where,” said an elderly man without even raising his head.

That was the beginning spark for Gary Glazner’s Alzheimer’s Poetry Project, a process he created to help engage and connect with those living with dementia through reading aloud and discussing poetry.

“There are four steps to the process,” Gary explains. “First, a call and response, where I read a line of poetry and the group echoes it. Then we discuss the poem. Next, we add props to the experience and finally, we create our own poem.”

A few of the familiar poems Gary uses include:

The Tyger—William Blake

The Owl and the Pussy Cat—Edward Lear

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod—Eugene Field

How do I Love Thee?—Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Purple Cow—Gelette Burgess

Jabberwocky—Lewis Carroll

Daffodils—William Wordsworth

His website, www.alzpoetry.com, is brimming with verse and rich with recommendations.

Gary has shared poetry with people living with dementia all over the world. His usual session lasts around an hour. He often centers his poems on a theme, such as Summer, Birds, Trees, or Food, and enriches the gathering with objects that engage the senses. For example, to supplement summer-time poetry, he might include a bucket of sand and a conch shell. He brings a misting spray to simulate an ocean breeze and lets people smell suntan lotion. For refreshments, he suggests fresh strawberries, lemonade, popsicles, or homemade ice cream. This four-step poetry process also works at home with just two care partners

“Poetry goes beyond the autobiographical memory and offers care partners a way to communicate with someone who has memory loss,” Gary says.

Good news for the Kansas City area: Gary is doing a poetry workshop here in early October. For more information, contact Deb Campbell at kcseniortheatre@gmail.com

For more information on Gary and the Alzheimer’s Poetry Project, visit www.alzpoetry.com

Gary’s book is a great resource: Dementia Arts: Celebrating Creativity in Elder Care

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Three Star-Studded Tips: The Creativity of Being a Care Partner

“For my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream.” Vincent Van Gogh

Several years ago, we spent an evening in Zion National Park in Utah looking for shooting stars.

“There’s one,” someone said.

“I see it!” someone else said.

I saw only the regular stars, which were also gorgeous but not quite as exciting.

“I can’t see any shooting stars,” I finally confessed.

“Here’s how you spot a shooting star,” our friend Ron told me. “You soften and widen your gaze and stare off into the middle distance. You’re looking at everything and nothing. That way you’re open to that sudden flash of light and movement.”

I didn’t see the flash of light from a shooting star that evening, but I did have an idea flash. Looking for shooting stars is like inviting out creativity. You open up your focus, relax, put yourself in receiving, daydreaming mode and wait for something marvelous.

For me, the art of being a care partner was an exceedingly creative endeavor. Much of the time was fraught with focus, dedicated to detail. But when I remembered to soften and widen my gaze, I was able to see my mom for the star she was, even when she seemed light years away from me.

Here are some tips for your own personal “star-gazing:”

Sit quietly with the person living with dementia. If appropriate, hold hands.

Let go of your history and your expectations. Appreciate her just as she is.

Open your mind and heart: be receptive to whatever flashes of light may come your way. Be happy even if you think nothing particular has happened.

For me, this was a rich way to connect with Mom when she was without words. Just sitting still renewed me, and ideas and memories often bubbled up.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Four Page-turning books

I have to say, I wasn’t really in the mood to read a memoir about the Alzheimer’s journey. But a friend recommended The Long Hello and I sat down to leaf through it. Four hours later, after both tears and laughter, I had completed the lyrical journey, an artful weaving of rational recall and poetic pouring. I could see and feel Cathie Borrie, the author, and I felt I knew her fanciful, magical, distracted, needy, exhausting, interesting mom. Cathie’s honesty and her ability to capture the intricate connections inherent in this dementia journey were like walking a familiar road through a mysterious jungle. This book is a burst of beautiful writing anchored by deep poignancy and meaning.

I have to say, I wasn’t really in the mood to read a memoir about the Alzheimer’s journey. But a friend recommended The Long Hello and I sat down to leaf through it. Four hours later, after both tears and laughter, I had completed the lyrical journey, an artful weaving of rational recall and poetic pouring. I could see and feel Cathie Borrie, the author, and I felt I knew her fanciful, magical, distracted, needy, exhausting, interesting mom. Cathie’s honesty and her ability to capture the intricate connections inherent in this dementia journey were like walking a familiar road through a mysterious jungle. This book is a burst of beautiful writing anchored by deep poignancy and meaning.

I also really enjoyed Martha Stettinius’ Inside the Dementia Epidemic: A Daughter’s Memoir. Meeting Martha and her mom on the pages of her searching memoir was like rediscovering old friends. I identified with Martha and I was also caught up in her story. I was moved by her struggle to truly care for and take care of her mother, while still preserving her soul and her family life. Martha did a great job of creating a compelling and readable story, while offering a wealth of practical tips and resources.

I also really enjoyed Martha Stettinius’ Inside the Dementia Epidemic: A Daughter’s Memoir. Meeting Martha and her mom on the pages of her searching memoir was like rediscovering old friends. I identified with Martha and I was also caught up in her story. I was moved by her struggle to truly care for and take care of her mother, while still preserving her soul and her family life. Martha did a great job of creating a compelling and readable story, while offering a wealth of practical tips and resources.

Several weeks ago, I wrote about my first visit to an Eden alternative home, the magical Sierra Vista in Santa Fe. The founder of Eden Alternative is Dr. Bill Thomas, who is one of the pioneers in making dementia care more home-like and person centered. His book, Life Worth Living: How Someone You Love Can Still Enjoy Life in a Nursing Home – The Eden Alternative in Action, is rich with ideas for care facilities. Home care partners can use his concepts to make their household even more creative and welcoming. As a bonus, Atul Gawande wrote about Dr. Thomas, in his fascinating book, Being Mortal. You’ll be inspired by Dr. Thomas’s innovation and his tenacity.

Several weeks ago, I wrote about my first visit to an Eden alternative home, the magical Sierra Vista in Santa Fe. The founder of Eden Alternative is Dr. Bill Thomas, who is one of the pioneers in making dementia care more home-like and person centered. His book, Life Worth Living: How Someone You Love Can Still Enjoy Life in a Nursing Home – The Eden Alternative in Action, is rich with ideas for care facilities. Home care partners can use his concepts to make their household even more creative and welcoming. As a bonus, Atul Gawande wrote about Dr. Thomas, in his fascinating book, Being Mortal. You’ll be inspired by Dr. Thomas’s innovation and his tenacity.

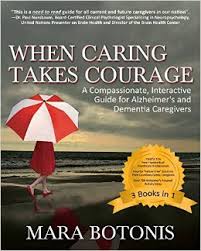

It’s not often that you read a book about dementia care and laugh. But when Mara Botonis wrote about carefully laying out supplies for a creative arts project, only to have her loved one staring out the window, then studiously plucking lint from his sweatpants, I had to laugh. I could see my beautiful mom doing exactly the same thing. Mara’s book, When Caring Takes Courage: A Compassionate, Interactive Guide for Alzheimer’s and Dementia Caregivers, is all about making the most of our moments together. Mara knows about dementia from her career in senior living and she has taken the personal dementia journey with her beloved grandfather. She orchestrated the book to make it easy for the exhausted care partner to problem solve and get instant help. She offers activities and projects for a range of abilities and situations.

It’s not often that you read a book about dementia care and laugh. But when Mara Botonis wrote about carefully laying out supplies for a creative arts project, only to have her loved one staring out the window, then studiously plucking lint from his sweatpants, I had to laugh. I could see my beautiful mom doing exactly the same thing. Mara’s book, When Caring Takes Courage: A Compassionate, Interactive Guide for Alzheimer’s and Dementia Caregivers, is all about making the most of our moments together. Mara knows about dementia from her career in senior living and she has taken the personal dementia journey with her beloved grandfather. She orchestrated the book to make it easy for the exhausted care partner to problem solve and get instant help. She offers activities and projects for a range of abilities and situations.

What books are spurring you onward these days? I’m immersed in writing my new book, tentatively titled Creativity in the Land of Dementia, so I’m focused on the topic in all its forms. The great news is that there are so many amazingly imaginative people out there, making the world a more connective and creative place for those living with dementia, their care partners, family, and friends. Which means, making the world better for all of us.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Six Easy Steps for Creating Art that Sends a Message

Art is the only way to run away without leaving home. ~Twyla Tharp

Reverend Katie Norris knows firsthand the power of a welcoming environment. She has learning disabilities and works better in a room free of distractions. When her mom, Carolyn Farrell, was diagnosed with dementia, Katie turned to art as a way to deepen their connection. Her art projects were so satisfying that she wrote a book, Creative Connections in Dementia Care, offering simple and meaningful ideas for engaging through the arts.

Katie grew up going to Montessori schools where everything had a place and the work area was clean. She flourished in that environment and realized her mom would flourish as well.

To prepare the room, Katie removed (or minimized) clutter. She added a lamp to increase the light and reduce shadows. She used brightly colored tablecloths so it was easy to see the art paper.

art paper.

Creating note cards is one of Katie’s favorite projects, since they are fun and easy, and result in a tangible, useful gift. If you have time, you can make a card in advance, so you’ll have an example to share. This is a relaxing activity for people of all abilities and does not require an artistic temperament. The complete recipe for notecards is in Katie’s book.

- To begin, set out the materials.

- Fold paper into the desired size. Or you can buy blank cards and envelopes at a hobby store.

- Decide if you each want to make your own cards. Or you can work together.

- Use paints or colors to create a free form design. If you’re working with someone who likes more structure, draw some bright lines on the card to form a simple design. They can then paint within and around the design or highlight the picture by outlining it with buttons, glitter, stickers, or paint. Demonstrate the options and leave plenty of space for creative unfolding.

- Extras include painting the background of the card with a little paint roller, called a brayer brush, adding design with sponge daubers, or gluing on pictures gleaned from old magazines and cards.

- People also enjoy decorating the envelope.

The notecards have a variety of uses, depending on the desires of the person living with dementia. You can donate them to churches or children’s hospitals, give them to friends and family, or frame the finished product for display. Or you can send your own notes on it.

“This project works well with an intergenerational group,” Katie says. “We involved our faith community, by asking them to host a button drive for us. That gave us a chance to share the finished products with them.”

Sharing this art helps people understand the vast creativity of those living with dementia.

For more information about Katie and her book, visit www.RevKatieNorris.com

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.