Archive for June 2014

Finding Our Hope, Again and Again

“People must decide to be hopeful despite all, and they must make this decision again and again.”

Stephen G. Post, PhD

Several months ago, our friend Mike Splaine suggested I read an article by Stephen Post, Director, Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care, and Bioethics. When I saw the words “the deeply forgetful,” my eyes filled with tears. Dr. Post truly honors and understands people who are living with dementia and their care partners. I’m sharing just a portion of his beautiful story of hope, with a link at the end, so you can read the rest.

HOPE IN CARING FOR THE DEEPLY FORGETFUL: ENDURING SELFHOOD AND BEING OPEN TO SURPRISES

Stephen G. Post

In the lives of carers for the deeply forgetful, hope might be best defined as “an openness to surprises.” Dementia, in its intractable, progressive, and irreversible form, is often caused by Alzheimer’s disease (about 60 percent of cases). There is much bleakness in the insidious pealing away of memories and capacities. Where is hope? Is there any at all?

The idea of hope as “being open to surprises” emerges from twenty years of working with carers in support groups and community dialogues. Yes, there is an assault on the story of a life, but despite the losses, there are also sporadic indicators of continuing self-identity that make caring meaningful.

The term demented is so often used in a derogatory manner, and lends itself to dehumanization and despair. The deeply forgetful suggests continuity with a shared humanity, for which forgetfulness is a problem of degree, from the absent-minded professor to the shopper who has forgotten where the car is parked, from the patient who has just awakened after shock therapy to the athlete who has suffered one too many concussions, from the young child whose capacities for memory have not yet developed to the adolescent with attention deficit disorder. We all have some problems with memory, but to varying degrees at different times. I recognize that classically “dementia” implies a precipitous decline from a former mental state, and has been sharply contrasted with “normal” age-related forgetfulness. But with such middle ground as “mild cognitive impairment” and the like, there is clearly a continuum involved. It is all a matter of degree.

Thank you to Stephen G. Post

Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Department of Preventive Medicine, Director, Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care and Bioethics

Please visit his site to complete the article and read more.

www.stephengpost.com

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Exploring the Creativity of Limitation: New Ways to Tell the Same Truth

My mother gets in the car and stares straight ahead.

Before I turn the key, I say, “Mom, want to put on your seatbelt?”

“What?” She has a sweet, vague look on her face.

“Your seat belt. You’ll need to put it on.”

I reach over her and drag down the seat belt. She nods and pulls it forward, towards the buckle. But she looses momentum and the belt slides back into oblivion. Now I have to unbuckle my own seat belt, stretch up and pull my mother’s seat belt forward again. This time I snap it in myself.

“How is work?” Mom says, when we are underway.

“It’s fine. I have an interesting new editing job, working on a romance novel.”

Mom smiles.

I stop at a red light and she asks, “How’s work?”

I grip the steering wheel but keep my voice calm. “Fine. I’m editing a romance novel.”

Three minutes later, she asks again. That’s when I realize; this is a great opportunity for me to exercise creativity. Having imposed limitations can be a catalyst for creative thinking. I set myself a challenge: How can I give my mother a new and truthful answer every time she asks me this question?

“How is work?”

“I am really enjoying reading this romance novel set in the early 20th century and figuring out how to make the characters more believable,” I say.

She smiles. I smile. Now that I’m viewing mom’s repetition as a trigger for my own creativity, I feel lighter, more open and loving. My mind is dancing about, constructing a new and interesting answer. Now I am eager for my mom to ask me again and again, so I can share interesting information with my mother while expanding my art of creative expression

Creative Pick Me Up: Ask yourself a question and create ten different true answers.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Staying Connected When a Friend Has Early Onset Dementia

It’s been two years since I’ve seen my friend who has early onset Alzheimer’s. When I learn she’s coming to town, I’m both excited and nervous: excited to see this charismatic, interesting and brilliant woman and nervous about communicating. Though she’s functioning very well, she’s told me her directional, reading and math skills have been impacted by the disease. How will her dementia affect our conversation?

We meet at a restaurant, hug, exchange a few pleasantries, and order our meals.

Then we look at each other. My brain is racing: what shall I say? How shall I start?

Finally, I pose the same questions I might ask any friend: “What is bringing you joy these days?’

She answers, eyes shining, telling me about her beloved husband, her stalwart friends, her garden and her meditation practice.

Then she tells me again about her meditation practice.

“I forget things sometimes, so don’t worry if I say the same thing twice,” she says.

My shoulders relax. I appreciate the honest and easy way she’s brought up the subject of dementia. Now I can ask, “What are you learning from your experiences?” Patience, acceptance, surrender, she says. By sharing the details, she’s helping me understand some of what she’s going through and allowing me to be a better and more compassionate friend.

Listen from Your Heart

Mary Cail, PhD, author of Alzheimer’s: A Crash Course for Friends and Relatives, offers this simple equation for compassionate communication during a visit:

- State the reality: I can’t imagine what it’s like to…

- Describe the situation: be in early dementia, etc.

- Say what you would like to do: I wish I knew what to say.

- Say what you can do: I can listen.

Then be quiet. As you listen, you’ll become more adept at knowing what to say. Chances are, just listening is enough.

Create Connection by Sharing and Listening

As you plan your visit, think about what your friend might need or want. Here are some additional ideas:

Bring something to share or to talk about. Sometimes reading a poem, story, newspaper article, depending on your friend’s interests, helps ease you into deeper conversation.

One man always brings a special rum cake and a Salsa CD for his friend: she’s in a care facility and often wants to dance. Another brings photos from their earlier adventures together. Another brings a grab bag with fun games, books, magazines and treats.

Bring a mutual friend with you. That widens the conversational possibilities.

Reach Out to Your Friend

Charlie and his wife Elizabeth have always had a wide circle of friends and Charlie’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s has not changed that. Here are some tips:

“The person with Alzheimer’s may not be able to initiate a get together,” Elizabeth says. She always appreciates it when Charlie’s friends call him. Early on, Elizabeth helped Charlie stay in touch with a call sheet that listed Charlie’s closest friends and their phone numbers.

Honor the relationship and Plan Your Visit

Many of Charlie’s friends are life-long. These friends always call Charlie first to plan a visit. Sometimes Charlie will say, “Better check with Elizabeth; she keeps the calendar.”

Other times, the friend will later check with Elizabeth and make sure she knows about the plan, as Charlie has a tendency to forget details.

Learn from the Spiritual Journey

Elizabeth helps Charlie with his social calendar and Charlie helps Elizabeth with her spiritual practice. “Charlie journals daily on acceptance and gratitude. He practices being grateful for the small things in life,” Elizabeth says. “I’ve learned a lot from him.”

………….

Mary’s book and blog:

Alzheimer’s: A Crash Course for Friends and Relatives

The All-Weather Friend Blog

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Father’s Day Tips: Four Fabulous Ways to Celebrate When Dad has Dementia

“Dad always liked a big Father’s Day celebration,” my friend told me. “But now he’s deep into dementia; I’m not sure he would notice.”

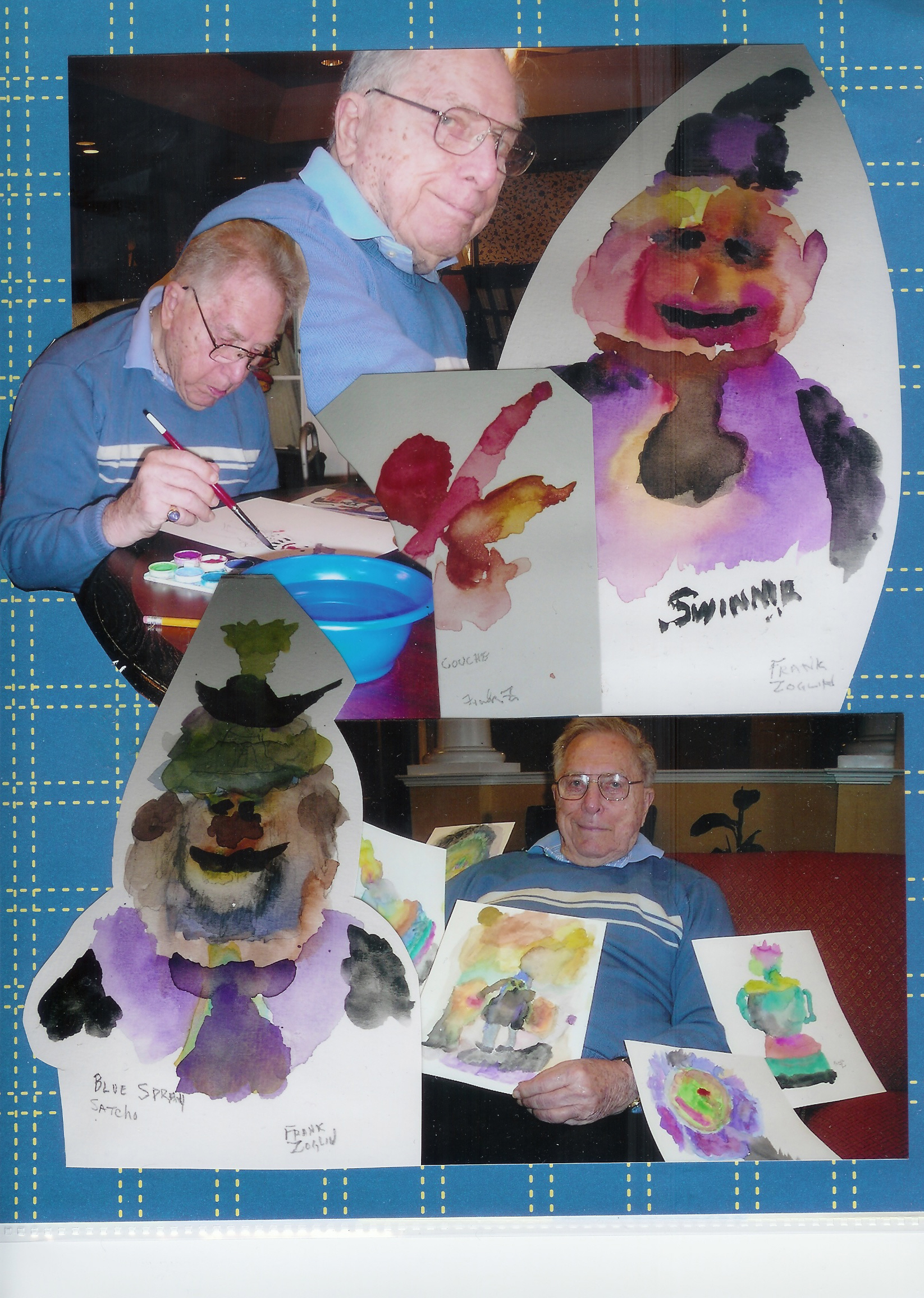

When Ron’s dad Frank relaxed into dementia, Ron and I often struggled with how to approach Father’s Day. Even though Frank didn’t know what day it was, we still wanted to honor Frank as a father. Here are some of the avenues we explored:

Reminiscing over Favorite Foods

We brought in a meal created from some of Franks’ current favorites and some gems from the past. Frank’s wife Mollie made her world-famous brownies and legendary rice pilaf. We bought cooked steaks and baked potatoes and as we ate, we talked about meals past. Inspired by the familiar tastes, smells and textures, Frank recited one of this favored old phrases: “I’m cool to other women but I’m hot tamale (Hot to Mollie.)”

Naming His Tunes

Frank and Mollie liked to dance occasionally and for one celebration, we printed out song lyrics and sang Frank and Mollie some of their old favorites. We didn’t sound like Sinatra or Fitzgerald as we warbled “It Had to be You,” or “Stardust” or “Three Coins in the Fountain” but we did sound sincere!

Ron and I created a HERO Project for Frank, a story-scrap book that incorporated highlights and photos from Frank’s life, along with a meaningful storyline. We also created one for Mollie. We read the HERO Projects with Frank and Mollie, using the stories as conversational catalysts. Frank enjoyed the experience; we enjoyed reading aloud with Frank and remembering shared experiences.

Celebrating Special Qualities and Life Lessons

As we sat together, we talked about some of Frank’s many stellar qualities, which included his easy-going nature, his natural charm, his entrepreneurial spirit, and his willingness to try new things. “Did I really do that?” Frank asked, as Ron described the bowling alley Frank and his brother owned and operated. “You did,” Ron said.“That was really something,” Frank said.

Frank’s comment summed up our Father’s Day celebration: it was really something. Just being together was wonderful. And taking time to really celebrate Frank with a tender mixture of food, photos, stories, and conversation was pure magic.

For more ideas on Naming His Tunes, please visit the exciting MusicandMemory.org

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.